Hum Sab Sahmat:

Resisting a Nation without Citizens

People all over the world –with few exceptions – have a curious tendency to celebrate anniversaries. The spread of the Georgian Calendar contributed greatly to the measure of life in such precise numbers. Lives in premodern times were a combination of the ordinary punctuated by the immense unpredictability of epidemics, famines and war. While marking special days and events became common, the temporal scales on which they unfolded varied greatly. Moreover, key events were located within a larger moral fabric and assessed in relation to an idealized progress. For instance, the Chinese measured time in the regnal era of their emperor within the “Mandate of Heaven” bestowed upon each dynasty. The length of a year was extended or shortened depending on the conditions of plenty or scarcity that may exist. In Indian history too, we find that the concept of time was expansive and not sterile. Long before dharma got wound up in ideas of upholding an ideal varnashrama, passage of time was measured in yugas that could last up to a 1000 years. Each said yuga was a measure of a moral order; a morality that placed the prerogative firmly on the ability of those who ruled to ensure the well-being of others. Time, in other words, was held accountable to material realities in which it existed. In the aforementioned traditions, and countless others such as these, anniversaries did not occur with predictable regularity but instead as a portend from a capricious ether.

We don’t live in those times anymore. For we have humbled time with great, mechanical precision. In the process we have exorcised all that is mythical, meaningful and moral about the times. Instead, we seemed to have entered a tacit social contract to create equally vapid spectacles to obfuscate the monotony that accompanies these anniversaries. The more pernicious the times, the grander the spectacle. And as a nation we are all approaching one such spectacle.

In 2022, independent India will mark seventy-five years of existence. Freedom did not come easily to the Indian Subcontinent. The ravages of the Second World War, made manifest most notably by the devastation of the Bengal Famine, and the subsequent mass dislocation and violence of the Partition made freedom a poignant moment. Many “Indians” witnessed the event from afar under continued conditions of captivity; conscripted as indentured labourers or prisoners of wars in many a colonial enterprises. Most others lived a life of humdrum humiliation in their own land – forced to mine an empire’s mineral fields, harvest its blood-soaked indigo and cotton, clear its forests and pick up shit in its dazzling urban complexes. And yet, 15th August 1947 was the day that began the process through which we – as a nation – could make good on our “solemn promise”. We were to build a new nation, not on rapacious extraction or demagoguery, but instead through a consensus.

Historians of a later era have often reminded us that “independence” was achieved through a series of seemingly disconnected episodes. To place all those episodes in a cogent narrative was not only arduous, it is quite possible that those episodes may never even align cleanly with each other. It is true that the nation that we built eventually, enshrined through an incredulous process of constitution-writing, was not a culmination of each of those episodic histories. But the memory of each struggle that made us free, regardless of the geography or social milieu of its circulation, informed what would be explicit and aspirational in our country. If universal adult franchise or abolition of caste discrimination seemed like an unavoidable point of departure, the realization of secularism, restoring ecological dignity and equity in access to resources presented itself as pathways to aspire towards.

India’s independence was a remarkable event not just for the millions of Indians but a lightening-rod for the rest of the colonized world. At its heart what made the Indian Path so significant was a recognition of how torturous, gradient and multivocal this journey was. It was, most important of all, alive and ongoing. Moreover, unlike many western-style democracies, subsequent decades and governments were assessed on the promise of the consensus and the deviations from it.

The consensus of 1947 is all but gone. It has been replaced by a shrill din that masquerades as the ‘new consensus’. It replaces the legacy of the freedom struggle with a sense of misplaced entitlement to conjure up an ill-fitted consensus. One which is so fragile that at the slightest suspicion of an ebbing support, it becomes viciously belligerent. It is hard to say who is this new consensus for. For there are farmers in hundreds and thousands protesting the state’s writ. There are roads that still carry the imprints of millions of migrant workers, inhumanly displaced in the name of public health. There are forests and mountains stripped of their human and non-human inhabitants alike. In this new India’s documentary raj, there are fewer citizens and greater threats. And finally, there is that one corpse who was defiled by the celebratory acrobatics of a local journalist.

We at Sahmat believe that the legacy of India’s freedom struggles was tenacious enough to defeat the British and build a nation on a collected set of ‘rights and wrongs’. We believe that that this tenacity will withstand the attacks it faces today from within. The onus lies with us to keep alive the shared heritage of our struggles – lived and remembered – and we shall overcome this moment of hate too. Far be it for us to invoke a false sense of nostalgia for a bygone nation, for we too know that previous versions of India were beset by their own limits. But we strive to ensure that the struggles of millions before us and those with us today are not turned into a mindless spectacle bereft of any meaning, any memory. We object to the commissions of crime in the name of an exclusionary consensus. We stand to defend and represent a greater moral world that produced our institutions, our forests and fields and indeed, us.

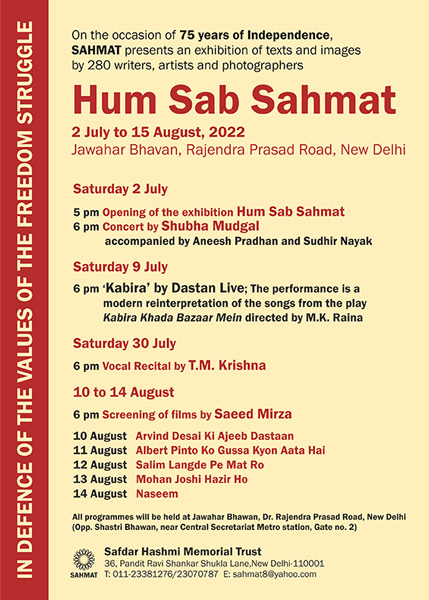

Customarily, we call upon artists, writers and other cultural figures of India to join us in creating a mosaic of expressions that turns the celebration of India’s 75th anniversary as a moment to take stock. To stop the juggernaut of madness in its tracks, to invoke our alternative visions for India and to infuse life by calling upon spirits and traditions from our pasts that treats transitions and passage in time as a moral critique of the present. In contributing your work of art for a year-long exhibition organized by Sahmat, let us speak of our many consensus, and our future desires.

-(Shatam Ray)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)